Observation and the production of the syncretic:

How the observation and reimagining of the archaic in fiction, produces an unstable present , and paves the way for alternative future societies.

Origins

Whilst walking beside a 13th century monastic fishing lake in North Yorkshire, I spotted a boulder on the waters edge that had fallen from the steep cliff sides of the valley above. I regarded the rock as I passed, my attention drawn to its structure in part due to a cavernous recession on its underside which was littered with chalk marks, the remnants of a climbers exertions. On the lower right hand side of the boulder (when looking North-East from the waters edge), I noticed an area of patterning on the rock which appeared strangely organised in form, yet nothing like the inflections left by a climber, or even a process of weathering. These markings were constructed of three distinct sections; A central group of concentric rings set into the surface of the stone, approximately forty centimetres in diameter. Directly above the centre of the main body, a group of much smaller rings around ten centimetres in diameter sat at the edge of the central section. Finally, ninety degrees to the right, again placed centrally on the edge of the main configuration, the third set of rings between ten and fifteen centimetres in diameter. At first, due to the alternation in bands of dark and light, the rings appear carved. The lighter sections, recessed, exposing a fresher hewn stone, the darker, the more prominent weathered surface. However upon touching the surface of the rock, my brain expecting to feel the sensation of ridges as my eye had predicted, the surface is uniform, the course grit texture, typical of the geology of the area. Stepping back, I observed that fissures in the rock had formed directly underneath and on the left side of the central section. The surface had deteriorated some time ago and was now coated in grey and green lichen. In this moment two possibilities came to mind as to the formation of this peculiar arrangement. I speculated that this group of markings could be the remnants of a carved stone cross, left by the monks which once constructed and inhabited this area of land. The second hypothesis was that these marks were the product of a now deceased cluster of lichen (most plausibly Rrhizocarpon Petreaum, a concentrically growing lichen species) that had coincidentally configured themselves to form this strangely geometric grouping. Both of these possibilities seemed and still seem today to be equally as plausible. I am able to picture, a monk, 800 years ago, carving into this rock a symbol of his faith and simultaneously, a group of microscopic organisms, slowly consuming the surface of this damp, South-West facing boulder. It is only through the passage of time that these theories and countless others have been clouded, coated in lichen, eroded away as more layers of potential are added with each year since there formation. Leaving us to reassemble half truths, fictions, from the fragments of exposed relics.

Observation

Firstly we must understand how our observations take place, so that we may seek to break down these processes and begin to regard our world from new perspectives. In the case of observing a familiar object, we begin by describing its form with our eyes, followed by a moment of estimation as our brain rummages through similar visual patterns. This is then satsified in a moment of recognition and ordinarily understanding as to the objects purpose.

In the case of an unfamiliar object, we begin again by observing the form, followed by estimation, only to be met with a speculative looping of imagination and recollection, attempting to salvage some sense of recognition, to ground our observations in other similar patterns or experiences. When this fails, it inevitably leads to a final process, invention, through which we bring to fruition our hypothesis as to an objects function or origin. These three key stages are: Observation, Speculation and Invention (OSI).

Being confronted by a novel or unrecognisable object leaves us suspended in a state of mind similar to what Korean Zen master, Seung Sahn Names, “don’t know mind”[1]. This is a position Zen Buddhist pupils are encouraged to attain. It represents a moment of surrendering your mind to a world of infinite potential, exposing our lack of true understanding, even of the most simple questions. For most this moment is fleeting, as our brains desperately try to contextualise all that we observe, leaping to conclusions based on our prior experiences. At times we connect unrelated dots, this process, triggeredspecifically by observation is known as “pareidolia”[2]. This process we may interpret as the formation of a type of fiction. One which is grounded in the irrational, the accidental misinterpretation and compilation of unknowable objects or images with previous experiences and patterns. These rare and almost always unplanned events present us with the a tabula rasa upon which to re-examine our surroundings, and the obects that populate them, and to reinvent how we might go forward amongst them.

Time

Time through its constant movement leaves behind that which is not maintained, coveted, scrubbed, fetishised and monitored. Temporal material builds on and over surfaces, providing a ground for multiple layers of potential interpretation to seed, which will in time grow to obscure an objects purpose. It is first through the creation of an object that this process begins, irrespective of its form or progenitors intention. Be it an art object (non-functional), appliance (functional) or by-product of a manufacturing process (passive). Each has as much potential to amass multiple explications through time as any other. For example, a line of three ancient standing stones, the ‘Devils Arrows’ located just off the A1, outside of Boroughbridge in North Yorkshire. Today such a series of objects, which may once have been considered appliances (part of a larger ritual landscape that follows the valley of the river Ure), have to all extents and purposes been removed from any contemporary knowable context. This has been facilitated by hundreds, even thousands of years of what Simon O’Sullivan calls, “accretion”. He uses this term to describe the development of a series of artworks through time. Specifically, the conversion of time itself from dormant substance, in which art objects are constructed, to a medium or “material”[3], which through its motion will warp and distort our perception of the object(s). In this way, our observation of the Devils Arrows, allows them to become new, as we understand we are looking at them from a distinctly different viewpoint to that of their creators. Their role cemented in our minds as simply relics of a far off time, devoid of contemporary functionality, waymarkers leading a path unknowable.

Uncertainty is a crucial part of viewing art, it is the bud from which imagination blossoms. This aforementioned sequence of observation, speculation and invention, provides us with a way of seeing entities, such as ancient stone monuments (the functions of which are not inherently obvious), from new or blank perspectives as. we are left out of tune with our prehistorical conciousness. This practice (which bares a vague resemblance to archeological analysis) has since the 1970s, become an increasingly popular method with which to critique and produce artwork. Lucy R. Lippard’ text, Overlay (1983), seeks to bring together the art of prehistory alongside the work of artists from 1960-80. She suggests “one of arts functions is to recall what is absent - whether it is history, or the unconscious… form, or social justice”. However the function of art in contemporary society is not so easily justified. Lippard argues that the attraction of prehistoric imagery is not only nostalgic but representative of our desires for a “time when what people made (art) had a secure place in their daily lives”[4]. Lippard’s conjuring or recollection of the absent, is a crucial aspect of what David Burroughs and Simon O’ Sullivan refer to as “mythopoesis”. The phrase initially coined by J. R. R. Tolkien, denotes:

“The generation of different worlds and communities that are the potential of, and alternatives to, existing worlds”[5].

This narrative style amalgamates past myth, fact and fiction as well as expectations of the future, in order to produce something “synchronic”[6]. That is to say through the manipulation of past and future, we are able to achieve something of this point in time, the now. As Burroughs and O’Sullivan suggest, we provide means for a “missing people”, a hypothetical future generation, to be “called forth”[7] into the world. Planting the seed for new avenues of experience to evolve from speculative fiction.

Becoming Lost

Processes of disorientation and confusion can be just as effective in promoting the consideration of new perspectives. In his book, The Image of the City (1990), Kevin Lynch discusses navigating heavily populated areas, and the modern phenomena of being unable to become lost through the use of “way-finding devices: maps, (and) route signs”. Due to these navigational aids, and since the texts publication, the growing presence of phones equipped with maps more sophisticated than the guidance system that took the first people to the moon, we are seldom without a sense of direction. However, should your phone run out of charge, finding yourself stranded on the other side of a city:

“the sense of anxiety and even terror that accompanies it reveals to us how closely it is linked to our sense of balance and well-being. The very word "lost" in our language means much more than simple geographical uncertainty; it carries overtones of utter disaster”[8].

This process of getting lost, should time and energy fascilitate, be relished. It affords us the rare oportunity to encounter the novel. But in the days of prehistory methods were put in place to prevent exactly this. Becoming lost may have been an event that would lead more often than not to danger, in a world devoid of the luxury of saftey we find in modern society. It is for this purpose that standing stones and cairns exist, to guide travellers across featureless, desolate landscapes. They are a point of reference, a way marker or “guide stoop”[9], within a landscape devoid of context.

Particularly in Yorkshire, the majority of these stoops were constructed in the latter half of the 1700s. Whilst bearing some resemblance to the neolithic/prehistoric structures such as the devils arrows, they are far better documented, their function cemented in our minds as navigational tools. Speculation around the properties and function, be it ritualistic or pragmatic, of these older megaliths is still ongoing. However, we may view the potential way marking aspect of these stones as an allegory for our understanding of our past. These objects are amongst some of our earliest known points of reference within the tangled matt of human history. Markers still visible on the horizon of time, nodding at where we have come from. Unknowable to us, yet all the more attractive because of this.

The Scots term “ken”[10] referring to both ones knowledge and understanding in addition to ones range of sight or vision, cements the idea of the limits of our perception or cognition, existing where our sight ends. We rely entirely upon our ability to see relics of our past in order for us to piece together where we have emerged from. To step outside of the ranges of our visual perception is to enter a world of uncertainty, rendering us lost.

Unconscious Orientation

When I came across the carving/lichen formation beside the lake, I was adamant that this was something significant, a relic from a time gone by that must be unraveled, irrespective of its origin. Is it simply part of the human condition that requires us to contextualise just what it is we are looking at? The phenomenon known as pareidolia which denotes “the tendency to perceive a specific, often meaningful image in a random or ambiguous visual pattern”[11], may have a large part to play in my observations. This cognitive (mis)interpretation of visual stimuli often referred to as “top-down”[12] cognition, provides ample evidence that humans have a tendency to rely absolutely upon unconscious bias in order to recognise and navigate complex visual imagery. In this way, as suggested by the study, ‘Attentional sensitisation of unconscious visual processing: Top-down influences on masked priming’ (2012), my prior knowledge of the lake as an ancient monastic site will have served as a “priming”[13] effect, leading me unconsciously to associate my surroundings with a religious iconographic semantic. In this way humans are predisposed to view their environment in ways that suit their world view, allowing our brains to actively fill the gaps in our understanding, thus simplifying our perception of our surroundings, so that we do not become overwhelmed by them. [If we apply this idea of priming to the viewership of art objects, the provision of an accompanying title, or written passage of context, provides a semantic within which to view an object, orienting how we observer a work in a specific direction, limiting the observers ability to view the object itself as blank or new. The idea of attempting to remove all context from an entity has lead to the production of Untitled works. This may be in part due to the desire of the artist to relinquish this prerequisite for context, making something that is simply of and for the world as the Constructivists desired. Or we may view it as an act for the sake of the viewer, to position them in a don’t know state, free of priming, able to interpret the work from any referential angle.]

The Sudo-Archaeological

Landscape photographer Henry Wessel maintains “the present is chaos”[14]. Wessel posits that we have the ability to chronologize and order both the past and future, the present however remains illusive, a shifting mass which is much harder to tie down. His fast instinctive method of shooting sees him rely heavily upon intuition with which he begins to “order chaos”[15]. He argues that it is an amalgam of the viewers lived experience, the form of the image and the viewers imagination which “shapes the meaning of the photograph”[16] (or artwork).

When we consider a gallery context, many cannot resist but ask the question why have we been presented with what we see before us. However for Wessel, it is vital that through a lack of context, the impetus is placed upon the viewer to extract both aesthetic beauty and analytical interest. It is this promotion of investigative observation and speculation which allows us to draw parallels between the examination of art objects and the taxonomic process of archeology. This practice is defined as, “the study of ancient cultures through examination of their buildings, tools, and other objects”[17]. The role of the viewer in contemporary art is not dissimilar. They are required to pick through the remains of a constantly evolving body of work, tracking the shifts and advancements in the artists interests and execution, drawing conclusions upon a works relation to the observers own world view and prior understanding of history. The sudo-archaeologist is born from simple curiosity and a desire to question what is seen before them, irrespective of the intention of the artist.

Unlike in true archaeology, our observations are not restricted to retrospection, instead we are able to access the speculative, predicting how a work may impact events which are yet to unfold, unconstrained by the endless search for truth. Our speculations simply require what Lippard quotes of notable esotericist John Mitchell, “an educated use of imagination”. Anyone has access to this heightened method of observing unknowable or art objects. At points lacking scientific rigour, but through its absence of bureaucratic rigidity, the sudo-archaeological provides a much broader field of influence and thus postulation. As Lippard goes on to say of the archeological community, “speculation about belief and value systems is avoided, even viewed with some embarrassment”[18], when viewing and analysing objects. By consciously placing ourselves as sudo-archaeological or OSI viewers, outside of the reaches of formal academic rigour, we have the ability to question the more ephemeral and unknowable aspects of our surroundings. This allows us to draw on a much wider pool of influences from which to base our conjectures, allowing us to explore the potential interconnectedness of seemingly disparate ontologies.

Sol LeWitt describes the position of conceptual artists as “mystics” in their ability to “leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach”. This process without a form of grounding in a single carefully illustrated intention, can lead one astray into the make believe, rather than to the formation of fiction in the sense of Burroughs and O’Sullivans mythopoeia. LeWitt continues to state that “irrational thoughts should be followed absolutely and logically”[19], in order to prevent this straying from the path of grounded mythopoeia. By following the irrational to its conclusion, we are able to explore potentially fictitious connections between the antiquated and the potential. This allows the present to constantly evolve into new objects and worlds for us to experience, manipulate and inhabit. For Wessel, it is his intuition which allows him to explore this realm of the irrational. It is the observation of his work, that produces an innate analysis of the America he presents for us, and thus the production of a form of mythopoeia in the mind of the observer. Through this we extract our own value in each work. I am lead back in time through his choice to display images captured several years prior to the point of exhibition. The temporal distance through which we recollect a landscape now altered by time, provides ample opportunity for the process of accretion to occur. We become aware that one day the places he has documented will succumb to the pressures of time and crumble as all great civilisations have.

Whilst photography, predominantly displayed indoors, can be maintained so that it its self is not subjected to weathering processes and further physical “accretion”, sculpture and surface based mediums displayed amongst the elements, not to mention, non-art objects and artefacts, are exposed to the constant battering of natural forces. This erosion becoming as much a part of how we observe the work as the medium with which it is constructed. Michael Heizer, recognised as one of the founding members of the land art movement, has in the last year completed construction of his monumental sculptural work, “City”, in the Nevada desert. This work has taken him over four decades to complete and cost over an estimated $25 million[20]. A mile and a half long by a quarter of a mile wide, the long snaking almost architectural complex, is constructed of mounds of gravel and dirt, as well as more formal concrete structures (“Complex 1” and “45, 90, 180”) informed by his earlier sculptural work. Today “city” is one of the largest artworks ever made. Heizer’s manipulation of the earth to reconstruct primitive forms, has been noted on many an occasion, even admitted by himself, to reference prehistoric earth work. “City”, through its size, enters into dialogue with such monumental structures as, the “Nazca Lines”[21] of Peru, the “Serpent Mound”[22] of Ohio and the Mayan “Quirigua Ruins”[23] of Izabal, Guatemala, amongst countless other ancient structures. Michaels father, Robert Heizer, a seminal archeologist who aided in the excavation of the “Quirigua Ruins”, is noted in a letter to Michael, to have compared the scales of the Mayan site with the newly constructed “Complex 1”[24].

The bunker like mound of “Complex 1”, equipped with sloping blast walls is a deliberate choice to aid the work in withstanding the detonation of an atomic bomb from the nearby Nevada nuclear test site[25]. “City” is built to last. Heizer’s admiration of the ancient Meso-American monuments goes beyond aesthetic value, to an appreciation of their resilience and ability to withstand the test of time. Through this we may interpret his choice of materials such as reinforced concrete, sand and soil, not simply as in keeping with the minimalist aesthetic, but as a desired intention to prolong the structures integrity. Despite this, in the four decades of construction, the work has already begun to show signs of wear, and with time, will no doubt become indistinguishable from a nuclear silo constructed in the 1950’s. Heizer perhaps unintentionally provides fuel for future misinterpretation of this mysterious and secretive site.

Scaling Uncertainty

For many artists scale or proportionality is fundamental to how they work and view the world around them. Despite the indisputable enormity of “city”, Heizer has said, “man will never create anything really large in relation to the world, only in relation to himself and his size”[26]. The scale of Heizers construction prevents us from absorbing a single image of the entire work. Instead like an architect, he provides lines for us to follow with both our eyes and bodies. Views framed by concrete shafts and mounds of gravel. Dirt slopes to contain and protect us. A terrain best suited for vehicular navigation, the long sweeping bends and ramps are reminiscent of a quarry access route or industrial site, perhaps due to the size of the machinery used to construct the landscape. Whilst it is possible to navigate the work on foot, the concrete curbs and elliptical cambered planes are of a racing semantic. I am reminded of the ancient track at Delphi, constructed for chariot racing at the “Pythian Games”[27]. We recognise elements of forms and yet are aware that this monument has no explicit function. This sensation leaves us in a state of wonder and awe, due predominantly to its size, the monument itself visible from a satellite. It is as though what we look at has already gone through a process of erosion, so that what we are left to observe is the bare bones of a once great monument which crumbled with time. We desire to adopt archaeological language in the hope of contextualising this primitive sprawling expanse of furrows and indentures. Its method of construction grounding us in a contemporary industrial setting, and yet its formation transports us to the past, to the prehistoric and simultaneously to the bunkers and silos of the cold war. This contention between and referencing of, the archaic and the modern, places us at the edge of uncertainty, stuck between recognition and speculation. Whilst we may view Heizer’s quest for scale as an ego driven fallacy of size is value, his work seeks to locate the sublime, simply by enveloping the viewer in an immaculate landscape. Through this, he provides us with a movement of art away from simple commodity, to an experience of wonder, mystery and speculation, both amplified and solidified by the unrivalled scale of “city”.

Richard Long states of his practice, “My work is about my senses, my instinct, my own scale and my own physical commitment”[28]. These philosophies for production seemingly amalgamate the involuntary aspects of Henry Wessel’s practice, with the human, world building desire to mould landscapes of Michael Heizer. The common aspect being the placement and scaling of the viewer in the world around them. Whilst this form of land art is not a new phenomena, particularly the desire to work “in the landscape”[29] (Michael Govan 2016) promotes the reintroduction of the human back into the natural, in a manner which is conducive to coexistence with the world around us. Instead of what many would deem to be the domineering and inconsiderate manner of the early land artists who’s constructions sought to reinforce the mastery of man of nature.

Since prehistory, humans have sought throughout time to describe and reflect nature in the hope that we may understand our place on this earth better. The constant that has dictated how we describe, measure and order the world around us has been our bodies, utilising its varying lengths as a scale to gauge our surroundings with. The yard, the distance of a single stride, is still used today but has been observed as a unit of measurement in megalithic cultures. Speculations suggest it found its origin in the erection and positioning of ancient stone monuments[30].

Artist and theoretician Elizabeth McTernan explores the fractal like nature of “the coastline paradox”, which suggests that “the length of the coastline depends on the method used to measure it”. In keeping with the ancient tradition of utilising body parts to measure, McTernan provides a step by step guide on how to calculate the length of a coastline in “handfuls”, describing the ordeal as a “necessary exercise in absurdity”[31]. This theme runs parallel to Longs desire to describe scale through repetitive physical commitment, exemplified in works such as, “Walking A Line In Peru 1972”[32], which requires hours of continuous motion to achieve the desired visual effect. His works, like cairns and stoops the world over, function simply as a marker of human presence within a landscape.

McTernan does not however wish to leave any visible trace of her efforts upon the ever shifting coastline which “will disappear as quickly as it arrives”. The only record of her effort is jotted in a notebook. The final number of hand lengths, left as a private “service to geography”, probes at the subjectivity of scientific methodology through the presentation of a more personalised, and perhaps more accessible unit of measurement. As the coastline paradox suggests, an objects size is only dictated by the method used to measure it. Through the subversion of contemporary recording techniques, we are reintroduced to a means of understanding our own scale and thus deepening our relation to the environment. In this case, one which places at the forefront, the direct integration of the human back into the landscape. Abandoning the satellite image and the formal scale to survey and categorise with the greatest efficiency.

The motivation for such an act is left entirely unexplained by McTernan, even suggesting we do not let ourselves “be sucked into the doom spiral of “why?”[31], Instead promoting that we should, “embrace the pointlessness” of such a futile act of mensuration. A meditation of scale, a performative act which sees the landscape leave a mark in the mind of the artist, rather than the inverse. This is a welcome change to a world which has for so long been littered with human detritus, suggesting that there is a place within art that promotes a humbling of the human, a movement from commodification, to consider that we are a part of nature, when so frequently we place ourselves outside or above it.

Mirroring a Different Life

“States, political and economic systems perish, ideas crumble, under the strain of the ages… But life is strong and grows and time goes on in its real continuity.” [33]

In 1920 the Realistic Manifesto sought to bring to rights art that could not withstand the “authenticity” of life. This is not to say they promoted the production of realistic, life like art, instead, they sought after art that was of the very “essence” of life itself. They posit that “Space and time are the only forms on which life is built and hence art must be constructed.” Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevzner questioned the ability of art to “withstand these laws if it is built on abstraction, on mirage and fiction”. Their aim, to set in motion the production of a new form of art, one that coexisted with life. For an object to be of and for life simultaneously. We witness a desire to move how we discuss and produce art into something more concrete than emotive and speculative, and thus allow arts impact on the world to become more resolute. This wish to ground art more formally in real life gave rise to constructivism, which sought to reflect the absolute nature of the ever growing modern industrial world. Through its mimicry of production lines, cars and aeroplanes, “a purely technical mastery and organisation of materials”[34], sought to provide a rigid platform for the generation of a new art form. This attempt was unsuccessful, as in the last 60 years we have come to accept more readily the chaotic, non linear nature of life itself and the scope this provides for the production of new modes of creation and experience that feed off precisely this lack of rigidity. Burroughs and O’Sullivan quote writer Jack Halberstam;

“Our task is not to shape this new life into identifiable and conforming forms, not to “know” this “newness” in advance, but rather... to impose upon the categorical chaos and crisis that surrounds us only ‘as much regularity and form as our practical needs require’”[35].

We may consider that conforming with predetermined tropes or “regulating chaos”[36] within the production of art objects prevents this uncertainty, limiting the prospect of future “accretion”, through solidifying the intention of a body of work or set of principles. Despite this, Burroughs and O’Sullivan suggest some semblance of recognition is required in the production of fictions so that we do not venture into escapism and away from the actuation of “futures different to that promised by existing regimes”[37]. In the case of Halberstam, grounding may risk the production of “over-determined fictions”, moving from what he describes as the “impractical as a space of possibility and newness”[38]. We may in this way observe that the reinterpretation of preexisting fictions, reviewed through a contemporary lens, provide space for such a movement toward different futures. This “impractical” space of re-evaluation is not dissimilar to the idea of uncertainty. Both describe a mental state of speculation, only now possible through accrued temporal distance and the desire for new or different circumstances. In this way, the production of fiction may have a real world affect on current affairs and stigmas. For example, Orion J Tracey’s science-fantasy novel, “The Virosexuals”(2020)[39], looks to broach the almost mythological subject of “Bug Chasing”, as both a “reclamation” of “taboo” acts and a process of healing through externalising trauma[40]. Tracey is successful in their amalgamation of real world, hard to air subject matter and fantastical speculative prose. This sudo-fictitious realm whilst entertaining, “call(s)[ed] forth” the possibility of not only a digital sphere sophisticated enough to contain all that is played out, but a world in which the long neglected reality of STD transmission and the persecution of those who contract AIDS, is brought to the forefront of conversation.

Determining Meaning

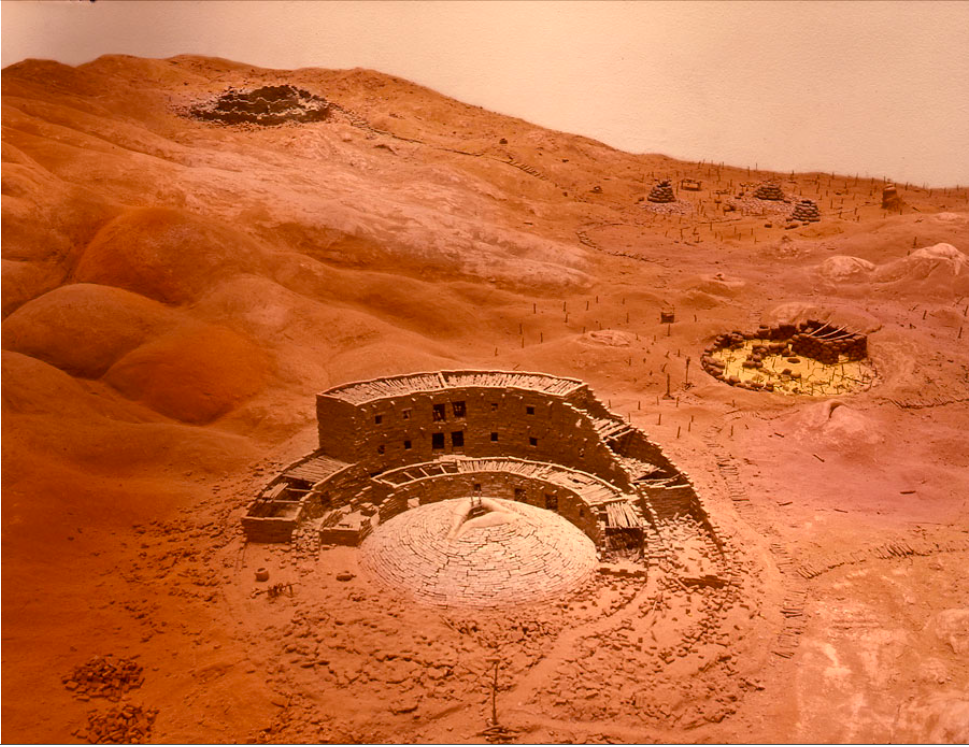

Returning to the idea of deterministic fictions, artist Charles Simmonds’(1945) is placed at the centre of his work, “Three Peoples”(1974-76)[41], particularly in our viewing of the written lore which seeks to inform how we regard his dwelling sculptures. Simmonds, born in New York, has throughout his career worked in urban landscapes the world over, producing miniature civilisations from clay and mud, who live and move amongst the ruins of old buildings and on street corners in migratory patterns. In, Three Peoples, we are introduced to a trio of civilisations through a text originally published for Samangallery, in Genoa (1975). The text describes the varying philosophies and histories which dictate their priorities within the landscape. The Linear People, in a constant state of movement, at points risking it all to wander back through the dwellings of the past. The Circular People, content with their orgiastic annual rituals, live in solitude, their lives dictated by regulations and a cycle of ceremonies. The Spiral People, seek to gamble with resources as they accelerate the production of great coiling towers toward a point of inevitable collapse, convinced their existence is contributing to the “most ambitions monument ever conceived by man”[42].

Through his writing, Simmonds provides a jumping of point for the viewers imagination, as we explore the possible interactions these various groups have with one another. We parallel our western society with the spiral peoples greed and ceaseless pursuit of progress in the name of capital gain. We observe the process of our movement through time in surreal physical metaphor as the Linear Peoples. The key to their identity and their past lays just back down the road in the dwellings of their ancestors. Here Simmonds materialises the idea of memory lane, he invites the imagining of a personalised and nostalgic trip back through our own past, prompting the question, where would my road take me? However we then regard his sculptural work we are immediately removed from the rose tinted introspection of years gone by, transported to an arid, hostile landscape, one devoid of life, littered with the crumbling ruins of past peoples. The decision to use raw, unrefined materials places the objects within a framework of antiquity, similar to Heizers work. Whilst Simmonds is the director of these various fictions, we understand that the majority of invention happens within the mind of the viewer, as we speculate around what we see based on the written context provided. This is only possible through the non-prescriptive nature of Simmonds narrative, in which he relinquishes control of the viewers interpretation, through gesturing toward a world larger than the one depicted within the physical work. We think of ruins of the world over, crumbling, left to decay, their functions obscure, lost in a cycle of rediscovery and appropriation, countless times over.

Becoming Myth

I believe temporal accretion, which facilitates our engagement with the impractical nature of the past, provides us with a ground upon which to piece together in fiction, alternative futures. This does not require a concrete mode. Instead, it will manifest in both digital and analogue forms, facing a variety of topics, more specific and unique than simply a mirroring of the world we inhabit currently. It is vital that the process of following and grounding pareidolia, no matter how seemingly removed from any knowable context it is, is carried out, as LeWitt suggests, “absolutely and logically”[43], to its conclusion. It is in this production of mythopoeia that we may begin to recollect “that which is absent”[44] and ground the subsequent fiction in the present.We witness a moving away from the prescriptive, utilising don’t know mind, as a means of both accepting our inability to answer fundamental questions and as McTernan states, to “embrace the pointlessness”[55], of the process of making art. To acknowledge that we do not have all the answers, placing an impetus on the viewer to directly engage with the work through exploiting Halberstam’s “impractical”[46].

I propose these speculative and fictive potentials set in place by our uncertainty in the past, will call forth future societies, with the possibility of their existence being more conscious of our place as humans. Integrated once more within the world, as in the days of prehistory. To no longer dominate but to provide an armature on which the living world can grow. To no longer dominate but to provide an armature on which the living world can grow.