A dull murmur fills the air. The shoulders and necks of the paying public surround you in a sea of black and blue, as umber light ricochets off freshly painted walls. People move in perfect aqueous unison, flowing from room to room with ruminative steps. You watch as those around you gravitate like moths toward keyholes of light projected onto walls and floors. Perfectly framed in these crisply lit apertures are objects. Some old, some new, all important enough to warrant their place in the light.

After some time following the current of bodies, drifting from spotlight to spotlight, a perfectly palm sized gold and ruby broach catches your eye. It sits in an anodised aluminium mount, an arms length away. Looking into the darkness beyond the stark lights, you glance toward the corner of the gallery. Your eyes adjust slowly, and you pick out the binary LED flick of a security camera. You follow the length of heavily painted cable extending from beneath the cameras casing, which disappears into the labyrinthine innards of a wall. You wonder for a moment, where does it go?

When was the last time you walked around a museum, gallery or other institution which houses objects of value? At some point, your eyes may have tired of the dead man’s work you have paid two hours wages to see. And as your mind wandered, did the paint begin to crack in front of you? Wood-worm begin to crumble gilt frames to sawdust and the canvas erupt with a thousand Webbing clothes moth larvae? Did wax busts effervesce in the midday sun and Pentelic marble Lapiths become gouged with valleys of red and green sublimate, left by a hundred years of rainwater.

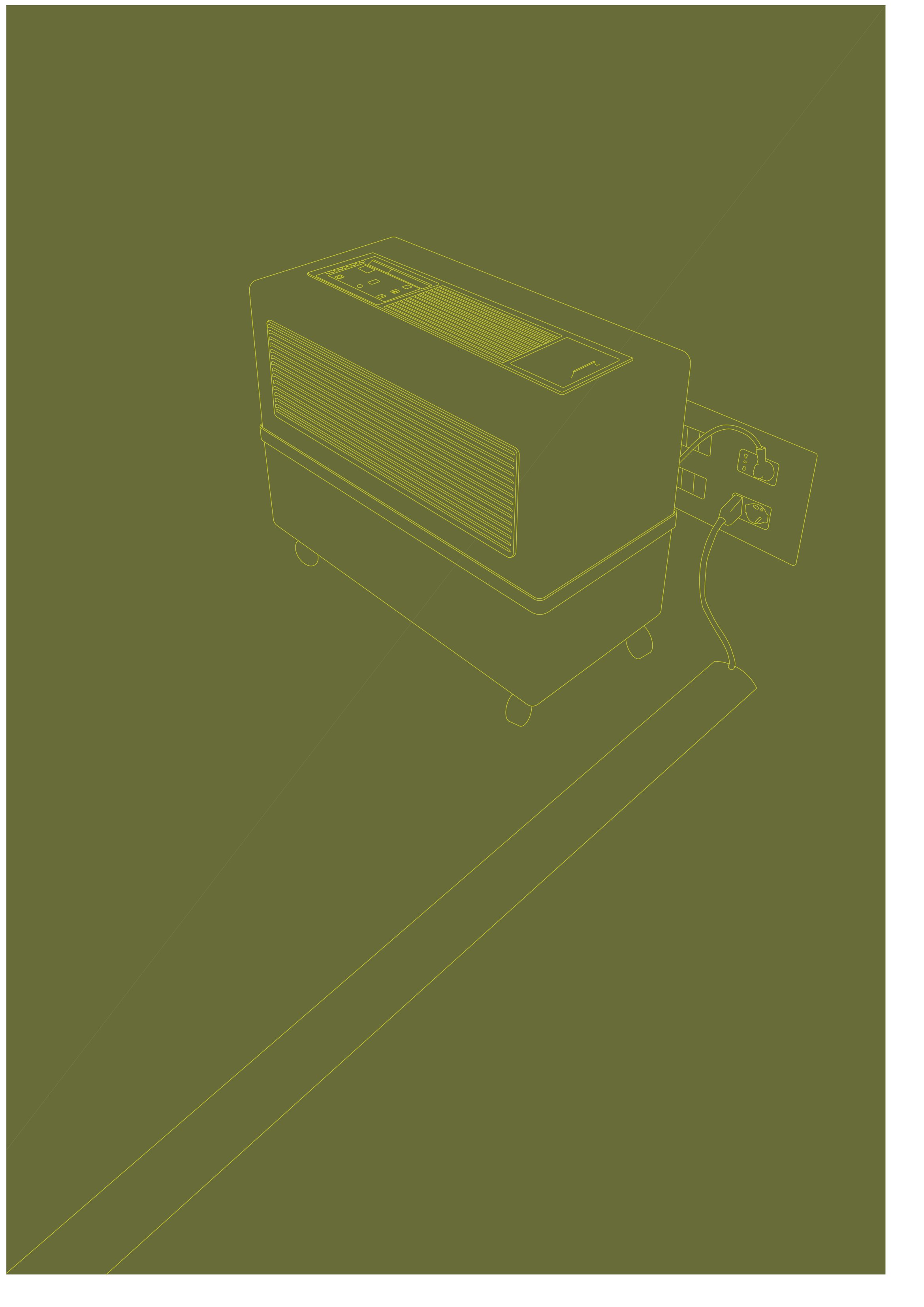

And when none of these things happened, did you peer behind a frame? Looking back into the shadow gap, you might have noticed a faded tan box with a glass faced dial, slipped snugly into its plastic holster. In the space between two sculptures, did you pause for a moment, your eyes passing over a neat concertina of striped card, bent into a prism? Or turning to examine the next painting, glance at the knee high plastic box, humming softly to itself amongst the shins of other gallery goers.

Once I saw these objects, positioned and coloured so as to draw as little attention to themselves as possible, I couldn’t help but notice them. Even the most minute objects are cast into stark relief against textureless walls. Incognito and yet incongruous, their forms are hard to ignore in such heavily fetishised and curated environments.

The function of the objects in question is to maintain the homeostasis of a museum or gallery. These regulatory systems are put in place by specialist conservators on behalf of institutions which house potentially unstable or corruptible assets. Such stringent monitoring systems are therefore predominantly used for historical objects. More specifically, objects which may have been historically exposed to damaging environments and contaminants, such as mould, an infestation of clothes moths or even dehydration. And whilst everyday entities and even the buildings that house the aforementioned objects crumble, we as humans have become increasingly concerned with the preservation of articles which allow us to recall a narrative surrounding our origins. Or rather, Institutions have become more concerned with the preservation of a particular history that they wish to perpetuate, situating themselves at the centre.

It has been known for institutions to consider other institutions storage conditions unsuitable for preserving historical artefacts, and as such, requisition objects so that they may be monitored more closely. Through surveillance and protection value is implicit, and thus more protection is requisite. This cycle has grown some museums to bloated masses, where, weighed down by their desire to control and protect, they are unable to display even 1% of their collection.

Picture for a moment one million square feet of darkened space, the temperature between 15.5°C & 21°C, the humidity kept below 60%. You walk down a narrow corridor which stretches toward the horizon. Either side of you tower grey laminate cupboards, and on every door, a table of contents is tucked into a softly yellowing line-bent acrylic plaque. The latin names of a thousand animals and plants taken from every corner of the earth are neatly printed in times new roman. The promise of You stretch out a palm toward a cool brass handle and pull, but the door is locked and the keys are nowhere to be found.